Because we're cleaning up the Love2learn site:

Trivia Questions on the Lord of the Rings and Middle Earth

These questions can be used with a Trivial Pursuit (TM) board game or the Trivial Pursuit (TM) Lord of the Rings edition. This work is in progress. Please submit additional questions in the comments. Have fun!

Last Updated: February 3, 2004

Categories:

[Names] [The War of the Rings] [Songs and Poems] [Middle Earth History] [The Hobbit] [J.R.R. Tolkien]

Names:

How did the ent Bregolad (Quickbeam) get his name?

By Answering another ent's question before they finished asking it.

What is Merry's full name?

Meriadoc Brandybuck

Who is the keeper of the prancing pony?

Barliman Butterbur

What elf came to the aid of Strider and the hobbits on their journey from Weathertop to Rivendell?

Glorfindel

What do the elves call Gandalf?

Mithrandir

Who is Sam's father?

Hamfast Gamgee

What does Eowyn mean?

horse joy

Who is Tom Bombadil's wife?

Goldberry

Where does Old Man Willow live?

The Old Forest

What alphabet (runes) is used by the language of Mordor?

the Elven alphabet

Give three alternate names for Aragorn?

Strider, Elessar, Elfstone, Wingfoot, Isildur's Heir, Thorongil, Estel, Telcontar, the Dunedan, Longshanks, the Renewer

Who are the two sons of Denethor and which is the elder?

Boromir and Faramir, Boromir is elder

Give three alternate names for Gandalf?

Incanus, Olorin, Tharkun, Lathspell, Grey Pilgrim, Grey Wanderer, Stormcrow, Greyhame, Mithrandir, Grey Fool, the White Rider

What were the two names Sam gave to Gollum?

Stinker and Slinker

Who are Butterbur's two workers?

Nob and Bob

What horse did Frodo ride to the Ford of Bruinen?

Asfaloth

Who were Aragorn's parents?

Arathorn and Gilraen the Fair

Who was Shelob's mother?

Ungoliant

Who is the Lord of Lothlorien?

Celeborn the Wise

Who is Denethor's father?

Ecthelion

Who keeps the Grey Havens?

Cirdan the Shipwright

Who is Legolas' father?

Thranduil

The Lord of the Nazgul dwells in which city?

Minas Morgul

What's another title for the Lord of the Nazgul?

the Witch King of Angmar

What is Treebeard's name for Lothlorien?

Laurelindorenon

Who was the first elf that Sam and Frodo met on their journey?

Gildor Inglorien

Whose foal was Snowmane?

Lightfoot's

Who were the twin sons of Elrond?

Elladan and Elrohir

Who are the three named orcs in Cirith Ungol?

Shagrat, Gorbag and Snaga

Who was Sharkey?

Saruman

What was Aragorn's sword, Anduril's, name before it was reforged?

Narsil

What is Imladris better known as?

Rivendell

The War of the Rings

Who did Smeagol kill in order to gain possession of the Ring?

his cousin Deagol

How many trolls did Strider and the hobbits see on their way to Rivendell?

three

What is Gollum's last word?

"Precious"

What were the two stairs of Cirith Ungol and which was more difficult?

the straight stair and the winding stair, straight was more difficult

Who made the prophecy that the Witch King of Angmar would not fall by the hand of man?

Glorfindel

What were the two alternative names for the New Row built after Sharkey's death?

Better Smials and Battle Gardens (It was a purely Bywater joke to refer to it as Sharkey's End)

Who said "Not lightly do the leaves of Lorien fall"?

Aragorn

From whom does Frodo learn that Boromir has died?

Faramir

What gift did Galadriel give to Gimli?

Three strands of her hair

What did the Ents lose?

The ent-wives

On what day of the year was the Ring destroyed?

March 25

Who did the Uruk-hai take prisoner after killing Boromir?

Merry and Pippin

What did Denethor have on his lap when Gandalf and Pippin came to him?

the horn of Boromir

What Tower did Sam rescue Frodo from?

The Tower of Cirith Ungol

Why did Sam reach Frodo in the Tower of Cirith Ungol without resistance?

Because most of the Orcs had killed each other

What was Galadriel's ring Nenya made of?

Mithril

According to Gandalf, how did Boromir escape the peril of his desire for the ring?

By his noble death in defending Merry and Pippin

Who greeted Gandalf, Theoden et al. after they arrived at Isengard from Helm's Deep?

Merry and Pippin

Who wore the three elven rings during the War of the Rings?

Elrond, Galadriel and Gandalf

How was Aragorn first recognized as the rightful king by the people of Minas Tirith?

Because of his ability to heal

What boy befriended Pippin in Minas Tirith?

Bergil son of Beregond

Who won the contest at Helm's Deep of the number of enemy killed (between Legolas and Gimli)?

Gimli

How did Gandalf escape from Orthanc?

He was rescued by Gwahir the eagle

Who first warns Gandalf that the black riders are on the move?

Radagast the Brown

Who did Merry and Pippin entangle themselves with in the Old Forest?

Old Man Willow

Songs and Poems of Middle Earth

What did Bilbo do the Lay of Gilgalad? He translated it. What is inscribed on the One Ring (roughly translated into the common tongue)?

One Ring to rule them all, One Ring to find them, One Ring to bring them all and in the darkness bind them

What is the next line after "of him the harpers sadly sing..." in the Fall of Gilgalad?

"the last whose realm was fair and free"

Name eight living creatures that Treebeard recites in his poem?

elves, dwarves, man, ents, beavers, bucks, bears, boars, hounds, hares, eagles, oxen, harts, hawks, swans and serpents

Middle Earth History

Who is older, Elrond or Treebeard?

Treebeard

What was Aragorn known as while living in Rivendell as a child?

Estel

Who built the tower of Minas Morgul?

the Numenoreans

Who cut the Ring from Sauron's hand?

Isildur

How many palantiri were there?

seven

The Uruk-hai are bred from what two species?

Orcs and Men

How many wizards are there?

5 (Radagast, Saruman, Gandalf and two unnamed)

How long did Bilbo possess the ring?

60 years

The Hobbit

How did Bilbo and the dwarves escape from the Trolls?

The Trolls argued until daylight at which time they turned to stone.

J.R.R. Tolkien

Where was J.R.R. Tolkien born?

South Africa

What character, according to J.R.R. Tolkien, didn't belong in C.S. Lewis' the Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe?

Father Christmas

Thursday, May 17, 2007

Thursday, May 18, 2006

Washington's Reply to the Congratulatory address of his Catholic fellow-citizens

Taken from Catholic Belief by Rev. Joseph Faa Di Bruno, copyright 1884

"Gentlemen--While I now receive, with satisfaction, your congratulations on being called, by an unanimous vote, to the first station in my country--I cannot but duly notice your politeness in offering an apology for the unavoidable delay. As that delay has given you an opportunity of realizing, instead of anticipating, the benefits of the general government,--you will do me the justice to believe that your testimony of the increase of the public prosperity enhances the pleasure which I should otherwise have experienced from your affectionate address.

I feel that my conduct, in war and in peace, has met with more general approbation than could reasonably have been expected; and I find myself disposed to consider that fortunate circumstance in a great degree resulting from the able support and extraordinary candor of my fellow-citizens of all denominations.The prospect of national prosperity now before us is truly animating, and ought to excite the exertions of all good men to establish and secure the happiness of their country, in the permanent duration of its freedom and independence. America, under the smiles of Divine Providence--the protection of a good government--and the cultivation of manners, morals, and piety--cannot fail of attaining an uncommon degree of eminence in literature, commerce, agriculture, improvements at home, and respectability abroad.As mankind become more liberal, they will be more apt to allow that all thos who conduct themselves worthy members of the community are equally entitled to the protection of civil government. I hope ever to see America among the foremost nations in examples of justice and liberality. And I presume that your fellow-citizens will not forget the patriotic part which you took in the accomplishment of their Revolution and the establishment of their government--or the important assistance which they received from a nation in which the Roman Catholic faith is professed.

I thank you, gentlemen, for your kind concern for me. While my life and health shall continue, in whatever situation I may be, it shall be my constant endeavor to justify the favorable sentiments which you are pleased to express of my conduct. And may the members of your society in America, animated alone by the pure spirit of Christanity, and still conducting themselves as the faithful subjects of our free government, enjoy every temporal and spiritual felicity.

George Washington March 12, 1790

"Gentlemen--While I now receive, with satisfaction, your congratulations on being called, by an unanimous vote, to the first station in my country--I cannot but duly notice your politeness in offering an apology for the unavoidable delay. As that delay has given you an opportunity of realizing, instead of anticipating, the benefits of the general government,--you will do me the justice to believe that your testimony of the increase of the public prosperity enhances the pleasure which I should otherwise have experienced from your affectionate address.

I feel that my conduct, in war and in peace, has met with more general approbation than could reasonably have been expected; and I find myself disposed to consider that fortunate circumstance in a great degree resulting from the able support and extraordinary candor of my fellow-citizens of all denominations.The prospect of national prosperity now before us is truly animating, and ought to excite the exertions of all good men to establish and secure the happiness of their country, in the permanent duration of its freedom and independence. America, under the smiles of Divine Providence--the protection of a good government--and the cultivation of manners, morals, and piety--cannot fail of attaining an uncommon degree of eminence in literature, commerce, agriculture, improvements at home, and respectability abroad.As mankind become more liberal, they will be more apt to allow that all thos who conduct themselves worthy members of the community are equally entitled to the protection of civil government. I hope ever to see America among the foremost nations in examples of justice and liberality. And I presume that your fellow-citizens will not forget the patriotic part which you took in the accomplishment of their Revolution and the establishment of their government--or the important assistance which they received from a nation in which the Roman Catholic faith is professed.

I thank you, gentlemen, for your kind concern for me. While my life and health shall continue, in whatever situation I may be, it shall be my constant endeavor to justify the favorable sentiments which you are pleased to express of my conduct. And may the members of your society in America, animated alone by the pure spirit of Christanity, and still conducting themselves as the faithful subjects of our free government, enjoy every temporal and spiritual felicity.

George Washington March 12, 1790

27th Amendment

When I was teaching the Constitution in my American History class to 7th and 8th graders in the fall of 1992, I was very interested to come across (in the World Almanac) the 27th Amendment which reads:

No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.

The most interesting thing was a little footnote that read:

"Proposed by Congress September 25, 1789; ratified May 7, 1992".

No other information was given. I went to the library to search for new articles on the topic. I couldn't find anything at my local library. When I went to a larger one I was able to discover three short articles - two tiny boxed paragraphs in Time and a one page story in People! With that introduction, I'd like to present to you the Story of the 27th Amendment - originally part of the Bill of Rights, but not ratified for more than 200 years.

The Amendment was proposed by James Madison and was among 12 amendments considered for the original Bill of Rights. We all know that ten were passed (the remaining proposed amendment related to the apportionment of Representatives). The amendment in question was passed by Congress in 1789 and then sent to the states for ratification. Three quarters of the states must ratifiy an amendment in order for it to take effect. Naturally the required number was much smaller in 1789 than in 1992. Six states had approved the measure before 1792, Ohio ratified it in 1873 and Wyoming in 1978. Thirty states ratified the amendment between 1983 and 1992. The man responsible for the renewed interest was a Texas resident named Gregory Watson, who launched a letter-writing campaign beginning in 1982. After Michigan became the final state to ratify the amendment on May 7, 1992, (and it was certified by U.S. Archivist Don. W. Wilson) the Senate President Pro Tempore, Robert C. Byrd (Democrat, West Virginia) sponsored a resolution preventing other amendments from being revived.

Addendum: When I first put these notes together on the Internet (on love2learn.net), around 1998 or1999, it was one of the few things available online about the remarkable 27th Amendment. Now there are dozens of sites with such information. Here are just a few examples (with further links on each site) - You can read more about Gregory Watson on Wikipedia. More on the 27th Amendment here.

No law, varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives, shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.

The most interesting thing was a little footnote that read:

"Proposed by Congress September 25, 1789; ratified May 7, 1992".

No other information was given. I went to the library to search for new articles on the topic. I couldn't find anything at my local library. When I went to a larger one I was able to discover three short articles - two tiny boxed paragraphs in Time and a one page story in People! With that introduction, I'd like to present to you the Story of the 27th Amendment - originally part of the Bill of Rights, but not ratified for more than 200 years.

The Amendment was proposed by James Madison and was among 12 amendments considered for the original Bill of Rights. We all know that ten were passed (the remaining proposed amendment related to the apportionment of Representatives). The amendment in question was passed by Congress in 1789 and then sent to the states for ratification. Three quarters of the states must ratifiy an amendment in order for it to take effect. Naturally the required number was much smaller in 1789 than in 1992. Six states had approved the measure before 1792, Ohio ratified it in 1873 and Wyoming in 1978. Thirty states ratified the amendment between 1983 and 1992. The man responsible for the renewed interest was a Texas resident named Gregory Watson, who launched a letter-writing campaign beginning in 1982. After Michigan became the final state to ratify the amendment on May 7, 1992, (and it was certified by U.S. Archivist Don. W. Wilson) the Senate President Pro Tempore, Robert C. Byrd (Democrat, West Virginia) sponsored a resolution preventing other amendments from being revived.

Addendum: When I first put these notes together on the Internet (on love2learn.net), around 1998 or1999, it was one of the few things available online about the remarkable 27th Amendment. Now there are dozens of sites with such information. Here are just a few examples (with further links on each site) - You can read more about Gregory Watson on Wikipedia. More on the 27th Amendment here.

Thursday, October 20, 2005

Songs from Shakespeare

from the 1911 Book of Knowledge: The Children's Encyclopedia (Grolier)

page 2915

The Fairy Life

from "A Midsummer Night's Dream"

Over hill, over dale,

Through bush, through brier,

Over park, over pale,

Through flood, through fire,

I do wander everywhere,

Swifter than the moon's sphere;

And I serve the fairy queen,

To dew her orbs upon the green;

The cowslips tall her pensioners be;

In their gold coat spots you see;

Those be rubies, fairy favours,

In those freckles live their savours;

I must go seek some dewdrops here,

And hang a peral in every cowslip's ear.

A Winter Song

from "Love's Labour's Lost"

When icicles hang by the wall,

And Dick the shepherd blows his nail,

And Tom bears logs into the hall,

And milk comes frozen home in pail,

When blood is nipp'd, and ways be foul,

Then nightly sings the staring owl,

To-who;

Tu-wit, to-who, a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel the pot.

When all aloud the wind doth blow,

And coughing drowns the parson's saw,

And birds sit brooding in the snow,

And Marian's nose looks red and raw,

When roasted crabs hiss in the bowl,

Then nightly sings the staring owl,

To-who;

Tu-wit, to-who, a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel (cool) the pot.

Under the Greenwood Tree

from "As You Like It"

Under the greenwood tree,

Who loves to lie with me;

And tune his merry note

Unto the sweet bird's throat.

Come hither, come hither, come hither;

Here shall he see

No enemy,

But winter and rough weather.

Who doth ambition shun,

And loves to live i' the sun;

Seeking the food he eats,

And pleased with what he gets.

Come hither, come hither, come hither;

Here shall he see

No enemy,

But winter and rough weather.

The Winter Wind

from "King Lear"

Blow, blow, thou winter wind,

Thou art not so unkind

As man's ingratitude;

Thy tooth is not so keen,

Because thou art not seen,

Although thy breath be rude.

Heigh-ho! sing heigh-ho! unto the gree holly;

Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly

Then, heigh-ho, the holly!

This life is most jolly.

Freeze, freeze, thou bitter sky,

That dost not bite so nigh

As benefits forgot;

Though thou the waters wwarp,

Thy sting is not so sharp

As friends remembered not.

Heigh-ho! sing heigh-ho! unto the green holly;

Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly;

Then, heigh-ho, the holly!

This life is most jolly.

A Fairy Lullaby

from "A Midsummer Night's Dream:

You spotted snakes, with double tongue,

Thorny hedgehogs, be not seen;

Newts and blind-worms, do no wrong;

Come not near our fairy queen.

Weaving spiders, come not here;

Hence, you long-legg'd spinners, hence;

Beetles black, approach not near;

Worm, nor snail, do not offence.

Philomel, with melody,

Sing in our sweet lullaby;

Lulla, lulla, lullaby, lulla, lulla, lullaby;

Never harm, nor spell, nor charm,

Come our lovely lady nigh;

So, good-night, with lullaby.

Orpheus and His Lute

from "King Henry VIII"

Orpheus with his lute made trees,

And the mountain-tops that freeze,

Bow themselves when he did sing:

To his music, plants and flowers

Ever sprung; as sun and showers

There had made a lasting spring.

Everything that heard him play,

Even the billows of the sea,

Hung their heads, and then lay by.

In sweet music is such art,

Killing care and grief of heart

Fall asleep, or, hearing, die.

page 2915

The Fairy Life

from "A Midsummer Night's Dream"

Over hill, over dale,

Through bush, through brier,

Over park, over pale,

Through flood, through fire,

I do wander everywhere,

Swifter than the moon's sphere;

And I serve the fairy queen,

To dew her orbs upon the green;

The cowslips tall her pensioners be;

In their gold coat spots you see;

Those be rubies, fairy favours,

In those freckles live their savours;

I must go seek some dewdrops here,

And hang a peral in every cowslip's ear.

A Winter Song

from "Love's Labour's Lost"

When icicles hang by the wall,

And Dick the shepherd blows his nail,

And Tom bears logs into the hall,

And milk comes frozen home in pail,

When blood is nipp'd, and ways be foul,

Then nightly sings the staring owl,

To-who;

Tu-wit, to-who, a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel the pot.

When all aloud the wind doth blow,

And coughing drowns the parson's saw,

And birds sit brooding in the snow,

And Marian's nose looks red and raw,

When roasted crabs hiss in the bowl,

Then nightly sings the staring owl,

To-who;

Tu-wit, to-who, a merry note,

While greasy Joan doth keel (cool) the pot.

Under the Greenwood Tree

from "As You Like It"

Under the greenwood tree,

Who loves to lie with me;

And tune his merry note

Unto the sweet bird's throat.

Come hither, come hither, come hither;

Here shall he see

No enemy,

But winter and rough weather.

Who doth ambition shun,

And loves to live i' the sun;

Seeking the food he eats,

And pleased with what he gets.

Come hither, come hither, come hither;

Here shall he see

No enemy,

But winter and rough weather.

The Winter Wind

from "King Lear"

Blow, blow, thou winter wind,

Thou art not so unkind

As man's ingratitude;

Thy tooth is not so keen,

Because thou art not seen,

Although thy breath be rude.

Heigh-ho! sing heigh-ho! unto the gree holly;

Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly

Then, heigh-ho, the holly!

This life is most jolly.

Freeze, freeze, thou bitter sky,

That dost not bite so nigh

As benefits forgot;

Though thou the waters wwarp,

Thy sting is not so sharp

As friends remembered not.

Heigh-ho! sing heigh-ho! unto the green holly;

Most friendship is feigning, most loving mere folly;

Then, heigh-ho, the holly!

This life is most jolly.

A Fairy Lullaby

from "A Midsummer Night's Dream:

You spotted snakes, with double tongue,

Thorny hedgehogs, be not seen;

Newts and blind-worms, do no wrong;

Come not near our fairy queen.

Weaving spiders, come not here;

Hence, you long-legg'd spinners, hence;

Beetles black, approach not near;

Worm, nor snail, do not offence.

Philomel, with melody,

Sing in our sweet lullaby;

Lulla, lulla, lullaby, lulla, lulla, lullaby;

Never harm, nor spell, nor charm,

Come our lovely lady nigh;

So, good-night, with lullaby.

Orpheus and His Lute

from "King Henry VIII"

Orpheus with his lute made trees,

And the mountain-tops that freeze,

Bow themselves when he did sing:

To his music, plants and flowers

Ever sprung; as sun and showers

There had made a lasting spring.

Everything that heard him play,

Even the billows of the sea,

Hung their heads, and then lay by.

In sweet music is such art,

Killing care and grief of heart

Fall asleep, or, hearing, die.

Wednesday, October 19, 2005

A Little History of Literature and the Poet Caedmon

"Literature" by Maurice Francis Egan

from the McBride Art and Literature Reader, Book 6, Copyright 1902

Literature is a verbal reflection of life. It is the only means by which we know how mankind in other times lived, thought, and acted. English literature includes all literature written in the English language.

In speaking of American literature, we must remember that it means many writings not in English. In South America and Mexico there are great authors who do not write the English language; and in Canada, which is part of America, there are numbers of writers of the French language deservedly celebrated.

Before the invention of the art of writing, or when only a few wrote, literature was perpetuated by tradition; it was handed down from father to son. Then the memory of man was his library. It is said that the works of Homer were preserved in this manner among the Greeks for five hundred years. Later, symbolical characters, or letters, were impressed on various substances, such as the bark of trees and prepared leaves. About the year 1471, books began to be printed in England, and the monks, who had laboriously preserved great masterpieces of literature by writing and illuminating them with wonderful care and taste, now learned to print by the aid of carved blocks and hand presses. Many of the terms now in use among printers may be traced to the printing-offices of the Benedictine monks, who eagerly made use of the new art. To the care of the monks we owe not only the preservation of the Bible, but of the Greek and Latin classics.

Verse was the earliest form of literature in all languages. The old English poetry was not in rhyme as we understand it. Alliteration and accents were essential.

The language in which the earliest English poems were spoken or sung differs much from the English of today. It was brought from Jutland, or Saxony, by the tribes who landed in Britain and drove the Britons, whom they called Welsh, into Wales and Cornwall, and into the part of France called Brittany. The latter preserve a separate language and literature to this day.

Later the stories of the Britons crept into English literature. The "Tales of King Arthur," on which Tennyson founded his great epic, was British, not Saxon. The Britons left us some Celtic words of domestic import or the names of places: avon and ex (meaning water), cradle, mop, pillow, mattock, crock, kiln, and a few others. Saxons probably married British wives, and hence we have the domestic British terms; but the majority of the Britons fled, leaving the land to the Saxon conqueror and his language.

The first English poems and the epic "Beowulf" were doubtless composed long before the seventh century, and taken from the Continent to England in the memory of Saxon bards. "Beowulf" was reduced to writing in the eighth century by a monk of Northumbria. "The Song of the Traveler," the earliest poem, enumerates the singer's experiences with the Goths. "Deor's Complaint" is a sad story of one who is made a beggar by war; it speaks of dumb submission to the gods.

"The Fight at Finnsburg" and "Waldhere" are, with "Beowulf," all the poems or parts of poems brought to England from the homes of the Saxons.

These fragments and the epic of "Beowulf" may be studied with the help of an Anglo-Saxon grammar. "Beowulf" is the story of a ferocious monster called Grendel. It was sung in parts, by the warriors at their feasts, each chanting a part. This monster, Grendel, like the dragons of the fairy tales, had the habit of eating human flesh. He harassed Hrothgar, Thane of Jutland, appearing in the banquet hall and devouring any guest that suited his fancy.

Beowful of Sweden sails to Jutland to assist the unfortunate king, and succeeds in killing the monster. "Beowulf," however, no more shows the worst spirit of the Saxon pagan than Sir Edwin Arnold's poem, "The Light of Asia," shows the selfishness of Buddhism. The Northumbrian Christian who transcribed it in 3,184 alliterative lines put the mark of his finer and gentler thoughts upon it.

To understand something of the spirit of the Teutonic tribes that began to make England, one might read Longfellow's Skeleton in Armor, and the Invasion, by Gerald Griffin, and Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott. In the last occurs the famous dialogue between Gurth and Wamba on the growth of the Norman, or corrupt Latin, element in the English language.

About the year 670, the first entirely English poem was written by Caedmon. It is a poetical paraphrase of the Old and New Testaments. It was written in Yorkshore, on a wind-swept cliff, in the abbey presided over by St. Hilda, a religious of noble blood. Caedmon was an elderly servant of the abbey, and when, after the feast, he was called on to sing in his turn, over his cup of mead, with the other servants, he refused because he had heard no songs that were not of cruelty and in praise of evil passions.

One night he crept away from the table, sad because the others jeered at him, and went to sleep in the cow-shed; and a voice in his dream said to him, "Sing me a song!" Caedmon answered that he could not sing; for that reason he had left the feast.

"You must sing!" said the voice. "Sing the beginning of created things."

Caedmon sang some lines in his sleep about God and the creation. He remembered these lines when he awoke. The Abbess Hilda, believing that his gift must come from God, had him taught sacred history, and he became a monk.

Caedmon's paraphrases are full of the poet's individuality. His description of the unholy triumph of Satan, when he succeeds in tempting Eve, is as striking as any passage in Milton's poem Paradise Lost, on the same subject. Caedmon's simplicity, naturalness, and deep religious feeling cause this ancient poem to be read and quoted by scholars today. It is said that the author died in 680 - a date which is also given as that of the death of St. Hilda, his friend and patroness. Caedmon gave the English a taste for the Old and New Testament. Caedmon's poems suggested to Milton the great epic, Paradise Lost.

from the McBride Art and Literature Reader, Book 6, Copyright 1902

Literature is a verbal reflection of life. It is the only means by which we know how mankind in other times lived, thought, and acted. English literature includes all literature written in the English language.

In speaking of American literature, we must remember that it means many writings not in English. In South America and Mexico there are great authors who do not write the English language; and in Canada, which is part of America, there are numbers of writers of the French language deservedly celebrated.

Before the invention of the art of writing, or when only a few wrote, literature was perpetuated by tradition; it was handed down from father to son. Then the memory of man was his library. It is said that the works of Homer were preserved in this manner among the Greeks for five hundred years. Later, symbolical characters, or letters, were impressed on various substances, such as the bark of trees and prepared leaves. About the year 1471, books began to be printed in England, and the monks, who had laboriously preserved great masterpieces of literature by writing and illuminating them with wonderful care and taste, now learned to print by the aid of carved blocks and hand presses. Many of the terms now in use among printers may be traced to the printing-offices of the Benedictine monks, who eagerly made use of the new art. To the care of the monks we owe not only the preservation of the Bible, but of the Greek and Latin classics.

Verse was the earliest form of literature in all languages. The old English poetry was not in rhyme as we understand it. Alliteration and accents were essential.

The language in which the earliest English poems were spoken or sung differs much from the English of today. It was brought from Jutland, or Saxony, by the tribes who landed in Britain and drove the Britons, whom they called Welsh, into Wales and Cornwall, and into the part of France called Brittany. The latter preserve a separate language and literature to this day.

Later the stories of the Britons crept into English literature. The "Tales of King Arthur," on which Tennyson founded his great epic, was British, not Saxon. The Britons left us some Celtic words of domestic import or the names of places: avon and ex (meaning water), cradle, mop, pillow, mattock, crock, kiln, and a few others. Saxons probably married British wives, and hence we have the domestic British terms; but the majority of the Britons fled, leaving the land to the Saxon conqueror and his language.

The first English poems and the epic "Beowulf" were doubtless composed long before the seventh century, and taken from the Continent to England in the memory of Saxon bards. "Beowulf" was reduced to writing in the eighth century by a monk of Northumbria. "The Song of the Traveler," the earliest poem, enumerates the singer's experiences with the Goths. "Deor's Complaint" is a sad story of one who is made a beggar by war; it speaks of dumb submission to the gods.

"The Fight at Finnsburg" and "Waldhere" are, with "Beowulf," all the poems or parts of poems brought to England from the homes of the Saxons.

These fragments and the epic of "Beowulf" may be studied with the help of an Anglo-Saxon grammar. "Beowulf" is the story of a ferocious monster called Grendel. It was sung in parts, by the warriors at their feasts, each chanting a part. This monster, Grendel, like the dragons of the fairy tales, had the habit of eating human flesh. He harassed Hrothgar, Thane of Jutland, appearing in the banquet hall and devouring any guest that suited his fancy.

Beowful of Sweden sails to Jutland to assist the unfortunate king, and succeeds in killing the monster. "Beowulf," however, no more shows the worst spirit of the Saxon pagan than Sir Edwin Arnold's poem, "The Light of Asia," shows the selfishness of Buddhism. The Northumbrian Christian who transcribed it in 3,184 alliterative lines put the mark of his finer and gentler thoughts upon it.

To understand something of the spirit of the Teutonic tribes that began to make England, one might read Longfellow's Skeleton in Armor, and the Invasion, by Gerald Griffin, and Ivanhoe by Sir Walter Scott. In the last occurs the famous dialogue between Gurth and Wamba on the growth of the Norman, or corrupt Latin, element in the English language.

About the year 670, the first entirely English poem was written by Caedmon. It is a poetical paraphrase of the Old and New Testaments. It was written in Yorkshore, on a wind-swept cliff, in the abbey presided over by St. Hilda, a religious of noble blood. Caedmon was an elderly servant of the abbey, and when, after the feast, he was called on to sing in his turn, over his cup of mead, with the other servants, he refused because he had heard no songs that were not of cruelty and in praise of evil passions.

One night he crept away from the table, sad because the others jeered at him, and went to sleep in the cow-shed; and a voice in his dream said to him, "Sing me a song!" Caedmon answered that he could not sing; for that reason he had left the feast.

"You must sing!" said the voice. "Sing the beginning of created things."

Caedmon sang some lines in his sleep about God and the creation. He remembered these lines when he awoke. The Abbess Hilda, believing that his gift must come from God, had him taught sacred history, and he became a monk.

Caedmon's paraphrases are full of the poet's individuality. His description of the unholy triumph of Satan, when he succeeds in tempting Eve, is as striking as any passage in Milton's poem Paradise Lost, on the same subject. Caedmon's simplicity, naturalness, and deep religious feeling cause this ancient poem to be read and quoted by scholars today. It is said that the author died in 680 - a date which is also given as that of the death of St. Hilda, his friend and patroness. Caedmon gave the English a taste for the Old and New Testament. Caedmon's poems suggested to Milton the great epic, Paradise Lost.

Friday, October 14, 2005

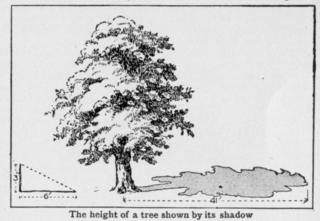

Measuring the Height of a Tree

There is a very easy way to measure the height of a wall, or a tree, or a church spire, that any boy or girl can use if he or she can do a sum in simple proportion. It is necessary that the sun should be shining at the time - that is all. Suppose that we have a tree, and the sun is shining, then the shadow of the tree is cast on the ground.

We must measure the distance from the extreme point of the shadow to the place right under the top of the tree. If the top point of the tree is right above the middle of the trunk, then we must calculate half the diameter of the trunk in making our measurements. Suppose that the distance from the point of the shadow to the trunk of the tree is 40 feet, and that the tree is 2 feet thick, then the total distance is 41 feet (40 feet plus half the diameter of the tree).

Now we take a stick, of which we know the exact length. Suppose that it is three feet long. We hold this upright with one end on the ground and notice how far its shadow extends. Then we measure the length of the stick's shadow, and perhaps find that it is 6 feet long. Now we multiply the length of the tree's shadow (41 feet) by the length of the stick (3 feet), and divide by the length of the stick's shadow (6 feet). The answer we get is 20 1/2, and we know that the tree is 20 1/2 feet high.

If we get odd inches in our measurements, we can work the sum out in inches instead of in feet. We can also get the answer - though not quite so correctly - by seeing how many steps it takes to go from the edge of the shadow to the tree, being careful to make our steps as nearly uniform as we can. Then, by measuring the length of one step, we can multiply its length by the number of steps, and find the distance. But in any measurement, whether it be a tree, or a church, or a wall, we must make sure that we take the distance to a point immediately under the highest point, so that if it be a church spire, for instance, we must make allowance for the distance between the wall up to which we measure and the centre of the church tower.

from the 1911 Book of Knowledge: The Children's Encyclopedia (Grolier)

page 1927

The Race from Marathon

from the 1911 Book of Knowledge: The Children's Encyclopedia (Grolier)

page 1803

"Rejoice, we conquer!" Gasping out these words as joyfully as his parched tongue can utter them, a poor worn-out youth drops lifeless into the arms of those Athenians who have hurried out of their city to learn his tidings. His faint whisper goes from mouth to mouth, and is passed on throughout an anxious city, quickening the pulses of the citizens until they lose themselves in an outburst of thanksgiving and rejoicing.

The story of this victory is one of the most thrilling the world has ever known. It takes us back over 2,000 years to one of the first decisive battles in the world's history. Darius, the Mede, has made himself master of Asia, and, angry at some interference on the part of some little Greek state, he assembles his picked soldiers, summons the various tribes who own his sway, and sails over the Aegean Sea to conquer and enthrall those little Greek states of whose skill in peace and war reports have reached him.

Athens is the first large city in the path of his hitherto unconquered hosts, and the Athenians feel the need of aid from the famous Spartans, whose state lay 120 miles to the south across the Isthmus of Corinth. The army of the Medes and Persians are fast approaching, and their city will soon be infested. How are the Spartans to arrive in time? The rulers of Athens, seated in grave council on the Acropolis, send for Pheidippides, their champion runner, who has won for his state the myrtle crown at the famous Olympic games held by the Greek states every five years. They command him to run and urge Sparta to come to their aid. And for two days and two nights Pheidippides runs, swimming the rivers and climbing the mountains in his path.

But the Spartans were envious and mistrustful of Athens. Though brave and fearless, they lacked intelligence; and besides, they were a very superstitious people, and so Pheidippides was sent hurrying back with the news that their army would come, but could not start until the full moon.

Pheidippides races back to Athens again. The Athenians were now thrown on their own resources. The Persians had landed and the Athenians resolved to oppose them at once. The weary but dauntless Pheidippides takes his long spear and his heavy shield, and marches with the 10,000 picked men to meet the foe. We read elsewhere of the famous battle of Marathon and how these 10,000 Greeks drove back hundreds of thousands of Medes and Persians; this story is of Pheidippides.

Marathon was fought and won, and the victorious Greeks called to Pheidippides to take the news to the capital. He flung down his shield, and ran like fire the long twenty-six miles to Athens. Then, bursting into the city, he fell and died, gasping as he fell the two Greek words which mean "Rejoice, we conquer!"

page 1803

"Rejoice, we conquer!" Gasping out these words as joyfully as his parched tongue can utter them, a poor worn-out youth drops lifeless into the arms of those Athenians who have hurried out of their city to learn his tidings. His faint whisper goes from mouth to mouth, and is passed on throughout an anxious city, quickening the pulses of the citizens until they lose themselves in an outburst of thanksgiving and rejoicing.

The story of this victory is one of the most thrilling the world has ever known. It takes us back over 2,000 years to one of the first decisive battles in the world's history. Darius, the Mede, has made himself master of Asia, and, angry at some interference on the part of some little Greek state, he assembles his picked soldiers, summons the various tribes who own his sway, and sails over the Aegean Sea to conquer and enthrall those little Greek states of whose skill in peace and war reports have reached him.

Athens is the first large city in the path of his hitherto unconquered hosts, and the Athenians feel the need of aid from the famous Spartans, whose state lay 120 miles to the south across the Isthmus of Corinth. The army of the Medes and Persians are fast approaching, and their city will soon be infested. How are the Spartans to arrive in time? The rulers of Athens, seated in grave council on the Acropolis, send for Pheidippides, their champion runner, who has won for his state the myrtle crown at the famous Olympic games held by the Greek states every five years. They command him to run and urge Sparta to come to their aid. And for two days and two nights Pheidippides runs, swimming the rivers and climbing the mountains in his path.

But the Spartans were envious and mistrustful of Athens. Though brave and fearless, they lacked intelligence; and besides, they were a very superstitious people, and so Pheidippides was sent hurrying back with the news that their army would come, but could not start until the full moon.

Pheidippides races back to Athens again. The Athenians were now thrown on their own resources. The Persians had landed and the Athenians resolved to oppose them at once. The weary but dauntless Pheidippides takes his long spear and his heavy shield, and marches with the 10,000 picked men to meet the foe. We read elsewhere of the famous battle of Marathon and how these 10,000 Greeks drove back hundreds of thousands of Medes and Persians; this story is of Pheidippides.

Marathon was fought and won, and the victorious Greeks called to Pheidippides to take the news to the capital. He flung down his shield, and ran like fire the long twenty-six miles to Athens. Then, bursting into the city, he fell and died, gasping as he fell the two Greek words which mean "Rejoice, we conquer!"

Thursday, October 13, 2005

The Spacious Firmament by Joseph Addison

[It's funny because we just came across a part of this poem in the lastest installment of The Happy Little Family series from Bethlehem Books.]

The spacious firmament on high,

With all the blue ethereal sky,

And spangled heavens, a shining frame,

Their great Original proclaim.

The unwearied sun, from day to day,

Does his Creator's power display;

And publishes to every land

The work of an almighty hand.

Soon as the evening shades prevail,

The moon takes up the wondrous tale;

And, nightly, to the listening earth,

Repeats the story of her birth:

Whilst all the stars that round her burn

And all the planets in their turn,

Confirm the tidings as they roll,

And spread the truth from pole to pole.

What though, in solemn silence all

Move round the dark terrestrial ball;

What though no real voice, nor sound,

Amidst their radiant orbs be found?

In reason's ear they all rejoice,

And utter forth a glorious voice:

Forever singing as they shine,

"The hand that made us is Divine."

Joseph Addison, a famous English writer, an essayist, a poet, a dramatist, and a statesman, was born in 1672 and died in 1719. He received the chief part of his school education at the "Charter House" and at "Queen's College." He is best known for his famous essays published in the Spectator, the Guardian, and the Tattler. His poem, "Peace of Ryswick," published in 1697, brought him a hundred pounds.

His essays are considered models of diction and are read by all who wish to acquire a polished style in writing.

from The Art and Literature Reader, Book 4, Copyright 1904

The spacious firmament on high,

With all the blue ethereal sky,

And spangled heavens, a shining frame,

Their great Original proclaim.

The unwearied sun, from day to day,

Does his Creator's power display;

And publishes to every land

The work of an almighty hand.

Soon as the evening shades prevail,

The moon takes up the wondrous tale;

And, nightly, to the listening earth,

Repeats the story of her birth:

Whilst all the stars that round her burn

And all the planets in their turn,

Confirm the tidings as they roll,

And spread the truth from pole to pole.

What though, in solemn silence all

Move round the dark terrestrial ball;

What though no real voice, nor sound,

Amidst their radiant orbs be found?

In reason's ear they all rejoice,

And utter forth a glorious voice:

Forever singing as they shine,

"The hand that made us is Divine."

Joseph Addison, a famous English writer, an essayist, a poet, a dramatist, and a statesman, was born in 1672 and died in 1719. He received the chief part of his school education at the "Charter House" and at "Queen's College." He is best known for his famous essays published in the Spectator, the Guardian, and the Tattler. His poem, "Peace of Ryswick," published in 1697, brought him a hundred pounds.

His essays are considered models of diction and are read by all who wish to acquire a polished style in writing.

from The Art and Literature Reader, Book 4, Copyright 1904

A Clever and Amusing Word Game

from the 1911 Book of Knowledge: The Children's Encyclopedia (Grolier)

page 2970

The game of doublets is an interesting word game that gives plenty of scope for skill and ingenuity, and enables us to exercise our memories and to make good use of our knowledge of words. Two words are chosen, each containing the same number of letters, and the words should be either of quite opposite meaning, as wrong and right, black and white, good and evil, rise and fall, and so on, or they should stand for things quite different from one another, as wood and iron, butter and cheese, soap and grease.

The game is to change one word into the other by changing only one letter at a time, and making a chain of words between the doublets. Two or three examples will make the method clear.

black

slack

stack

stalk

stale

shale

whale

while

white

tame

time

tile

wile

wild

shoe

shot

soot

boot

beef

been

bean

beak

peak

perk

pork

cat

cot

dot

dog

more

lore

lose

loss

less

black

block

clock

click

chick

chink

chine

whine

white

It will be seen by these examples that only one letter is altered in each word to make the next, and every change makes an actual dictionary word. It is not allowable to make a change of a letter that will produce something that is not a real word. For instance, we might have changed beef into pork like this: beef, boef, boek, bork, pork. That, of course, would be wrong, as no such words as boef, boek, bork, exist.

Then the transformation from one word to the other must be made with as few changes as possible. In changing from black to white we might have proceeded like this: black, block, clock, click, chick, thick, think, thine whine, white; but here we make eight words in between, and not more than seven are needed.

It must, of course, be understood that in changing one letter to make a new word in the chain, the substituted letter must occupy exactly the same position in the new word that the discarded letter did in the old word. Thus we can change bean into bran, but not into barn, for e being the second letter in bean, r must be the second letter in the new word, as it is in bran.

page 2970

The game of doublets is an interesting word game that gives plenty of scope for skill and ingenuity, and enables us to exercise our memories and to make good use of our knowledge of words. Two words are chosen, each containing the same number of letters, and the words should be either of quite opposite meaning, as wrong and right, black and white, good and evil, rise and fall, and so on, or they should stand for things quite different from one another, as wood and iron, butter and cheese, soap and grease.

The game is to change one word into the other by changing only one letter at a time, and making a chain of words between the doublets. Two or three examples will make the method clear.

black

slack

stack

stalk

stale

shale

whale

while

white

tame

time

tile

wile

wild

shoe

shot

soot

boot

beef

been

bean

beak

peak

perk

pork

cat

cot

dot

dog

more

lore

lose

loss

less

black

block

clock

click

chick

chink

chine

whine

white

It will be seen by these examples that only one letter is altered in each word to make the next, and every change makes an actual dictionary word. It is not allowable to make a change of a letter that will produce something that is not a real word. For instance, we might have changed beef into pork like this: beef, boef, boek, bork, pork. That, of course, would be wrong, as no such words as boef, boek, bork, exist.

Then the transformation from one word to the other must be made with as few changes as possible. In changing from black to white we might have proceeded like this: black, block, clock, click, chick, thick, think, thine whine, white; but here we make eight words in between, and not more than seven are needed.

It must, of course, be understood that in changing one letter to make a new word in the chain, the substituted letter must occupy exactly the same position in the new word that the discarded letter did in the old word. Thus we can change bean into bran, but not into barn, for e being the second letter in bean, r must be the second letter in the new word, as it is in bran.

Wednesday, October 12, 2005

The Names of Our Lady by Adelaide A. Procter

from the Art and Literature Reader, Book 4, copyright 1904

Through the wide world thy children raise

Their prayers, and still we see

Calm are the nights and bright the days

Of those who trust in thee.

Around thy starry crown are wreathed

So many names divine;

Which is the dearest to my heart,

And the most worthy thine?

Star of the Sea! we kneel and pray

When tempests raise their voice;

Star of the Sea! the haven reached,

We call thee and rejoice.

Help of the Christian! in our need

Thy might aid we claim;

If we are faint and weary, then

We trust in that dear name.

Our Lady of the Rosary!

What name can be so sweet

As what we call thee when we place

Our chaplet at thy feet.

Bright Queen of Heaven! when we are sad,

Best solace of our pains;-

It tells us of the badge we wear,

To live and die thine own.

Our Lady dear of Victories!

We see our faith oppressed,

And, praying for our erring land,

We love that name the best.

Refuge of Sinners! many a soul,

By guilt cast down, and sin,

Has learned through this dear name of thine

Pardon and peace to win.

Health of the Sick! when anxious hearts

Watch by the sufferer's bed,

On this sweet name of thine we lean,

Consoled and comforted.

Mother of Sorrows! many a heart

Half-broken by despair

Has laid its burden by the cross

And found a mother there.

Queen of all Saints! the Church appeals

For her loved dead to thee;

She knows they wait in patient pain

A bright eternity.

Fair Queen of Virgins! thy pure band

The lilies round thy throne,

Love the dear title, which they bear,

Most that it is thine own.

True Queen of Martyrs! if we shrink

From want, or pain, or woe,

We think of the sharp sword that pierced

Thy heart, and call thee so.

Mary! the dearest name of all,

The holiest and the best;

The first low word that Jesus lisped

Laid on His mother's breast.

Mary! the name that Gabriel spoke,

The name that conquers hell;

Mary! the name that through high heaven

The angels love so well.

Mary! our comfort and our hope,-

O may that word be given

To be the last we sigh on earth,

The first we breathe in heaven.

Adelaide Anne Procter, an English poet, was born in London, October 30, 1852; died in London, February 3, 1864. She was a daughter of the writer Bryan Walter Procter (Barry Cornwall). Her poetry is popular and some of her poems have been translated into several languages. Her first published articles appeared in a magazine edited by Charles Dickens. In the year 1851 she became a Catholic, and from that time on her writings show her bent of mind, the desire to do all things possible for God.

Through the wide world thy children raise

Their prayers, and still we see

Calm are the nights and bright the days

Of those who trust in thee.

Around thy starry crown are wreathed

So many names divine;

Which is the dearest to my heart,

And the most worthy thine?

Star of the Sea! we kneel and pray

When tempests raise their voice;

Star of the Sea! the haven reached,

We call thee and rejoice.

Help of the Christian! in our need

Thy might aid we claim;

If we are faint and weary, then

We trust in that dear name.

Our Lady of the Rosary!

What name can be so sweet

As what we call thee when we place

Our chaplet at thy feet.

Bright Queen of Heaven! when we are sad,

Best solace of our pains;-

It tells us of the badge we wear,

To live and die thine own.

Our Lady dear of Victories!

We see our faith oppressed,

And, praying for our erring land,

We love that name the best.

Refuge of Sinners! many a soul,

By guilt cast down, and sin,

Has learned through this dear name of thine

Pardon and peace to win.

Health of the Sick! when anxious hearts

Watch by the sufferer's bed,

On this sweet name of thine we lean,

Consoled and comforted.

Mother of Sorrows! many a heart

Half-broken by despair

Has laid its burden by the cross

And found a mother there.

Queen of all Saints! the Church appeals

For her loved dead to thee;

She knows they wait in patient pain

A bright eternity.

Fair Queen of Virgins! thy pure band

The lilies round thy throne,

Love the dear title, which they bear,

Most that it is thine own.

True Queen of Martyrs! if we shrink

From want, or pain, or woe,

We think of the sharp sword that pierced

Thy heart, and call thee so.

Mary! the dearest name of all,

The holiest and the best;

The first low word that Jesus lisped

Laid on His mother's breast.

Mary! the name that Gabriel spoke,

The name that conquers hell;

Mary! the name that through high heaven

The angels love so well.

Mary! our comfort and our hope,-

O may that word be given

To be the last we sigh on earth,

The first we breathe in heaven.

Adelaide Anne Procter, an English poet, was born in London, October 30, 1852; died in London, February 3, 1864. She was a daughter of the writer Bryan Walter Procter (Barry Cornwall). Her poetry is popular and some of her poems have been translated into several languages. Her first published articles appeared in a magazine edited by Charles Dickens. In the year 1851 she became a Catholic, and from that time on her writings show her bent of mind, the desire to do all things possible for God.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)